I have been thinking about Sir Thomas Browne lately. This has to do with stumbling upon a remark in Edmund Gosse's book, quoted in Lytton Strachey's essay, quoted in turn in Enemies of Promise [re which see also]:

The study of Sir Thomas Browne, Mr. Gosse says, 'encouraged Johnson, and with him a whole school of rhetorical writers in the eighteenth century, to avoid circumlocution by the invention of superfluous words, learned but pedantic, in which darkness was concentrated without being dispelled.'It is difficult, nowadays, to imagine that those last clauses were ever an indictment; one can hardly think of a more inviting description. (This is a coincidence; "darkness" is a poorly chosen word, it is quite wrong for the gong-like "pedantries" of Johnson, but by a sort of hypallage it fits Browne, who cared, like Donne, for the "echoes and recesses" of words.)

Browne initially seemed to me a less dynamic and therefore less interesting writer than Donne (whose special effects are every bit as good); they are similarly metaphysical -- Johnson partially defends both on the grounds that they said strange things because they had strange minds; their illustrations were "far-fetched but worth the carriage" -- but Donne is a more wide-ranging (even within the scope of a paragraph) and therefore less distinct figure. I am coming to realize, however, that it's possible to find Browne more interesting because his work is so much more "deliberate" and his range so much narrower. Two notes on this:

1. The direct influence of Browne on twentieth-century literature (much greater than that of Donne, I feel): the three figures that immediately come to mind are Borges, Sebald, and the Moore-Clampitt tradition of (American, mostly female) essayistic poets. That Browne's influence has been strongest on non-Anglophone writers is puzzling if you see him chiefly as a master of cadence and "brushwork," as Strachey does. It is, or ought to be, a truism that good work is more translatable than you think. Or perhaps it is better to put it this way: the part of someone's work that's likely to have a direct influence on others, i.e., whatever is imitable, can usually be translated; moments of high intensity, or of ineffable prettiness as in Campion, can neither be imitated nor translated.

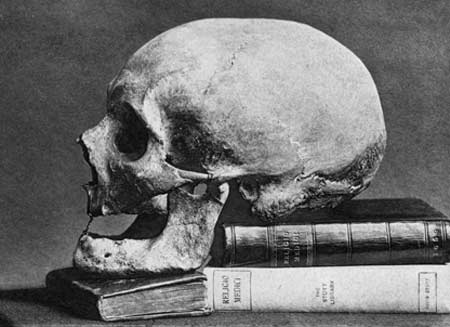

It is not surprising that Borges was fond of Browne; the Pseudodoxia -- qua anti-encyclopedia -- is like something out of a Borges story, and the dottiness re quincunxes in the Garden of Cyrus is of a piece with this (see also: the garden of forking paths, where the quincunx, I suppose, has been retrenched to a Mercedes-Benz sign). Gosse's remark is relevant, too; "darkness was concentrated without being dispelled," if anywhere, in that sentence about the man who disembarked unseen in the "unanimous night." With Sebald the affinities are too many to mention -- both lived in Norfolk; both were interested in skulls and mazes; both achieve a sense of autumnal repleteness and desolate fulfillment to which their accumulations of fact, the overflowing larders and cozy lumber-rooms of their minds, are essential (Donne, like the weather in the midwest, is neither cozy nor predictable enough).

2. As for Moore and Clampitt, there are echoes of Browne (as there allegedly are in Rae Armantrout), and there's also some commonness of purpose. There is, in particular, the shared naturalism; as Lytton Strachey says about Browne:

this strongly marked taste for curious details was one of the symptoms of the scientific bent of his mind. For Browne was scientific just up to the point where the examination of detail ends, and its coordination begins. He knew little or nothing of general laws; but his interest in isolated phenomena was intense. ... He cannot help wondering: ‘Whether great-ear’d persons have short necks, long feet, and loose bellies?’ ... Browne, however, used his love of details for another purpose: he co-ordinated them, not into a scientific theory, but into a work of art.

This is, I think, part of what many Moore and Clampitt poems attempt to do, but it is also quite close to what the Metaphysical poets were striving for. Why Browne rather than Donne, though; why cunctation over celerity? I think Virginia Woolf makes the essential point:

the publicity of the stage and the perpetual presence of a second person were hostile to that growing consciousness of one’s self, that brooding in solitude over the mysteries of the soul, which, as the years went by, sought expression and found a champion in the sublime genius of Sir Thomas Browne. His immense egotism has paved the way for all psychological novelists, auto-biographers, confession-mongers, and dealers in the curious shades of our private life. He it was who first turned from the contacts of men with men to their lonely life within. “The world that I regard is myself; it is the microcosm of my own frame that I cast mine eye on; for the other I use it but like my globe, and turn it round sometimes for my recreation.”Donne never does this for long; even in the poems, the voice tends to imply a dramatic context in which it is performing. But then Donne was not an eccentric, a recluse, or a marginal figure, as many of the great female poets have been; it is natural to be self-absorbed when one has no audience, and it is natural, when writing to oneself, to accrete and elaborate. Clampitt is explicit about her preferences:

precision and attention to detail are what Marianne Moore’s work is all about. And that is what I found attractive: a clear and principled opposition to the dictum of Dr. Johnson that poetry ought not to “number the streaks on the tulip.”And the other thing poss. worth saying is that Browne's approach to autobiography -- I am thinking mostly of the Garden and the Pseudodoxia, though perhaps Urn-Burial counts -- is an indirect one, the burden of self-disclosure is absorbed into the texture of the prose, and never explicitly assumed or answerably fulfilled. (I doubt that this was intentional on Browne's part, he would surely have asked to see the glass flowers at Harvard -- which, by the way, I have not.) I can't remember if I ever posted about the bowerbird aspects of blogging, but for some types of people there is something very satisfying about an approach to self-definition that is so thoroughly externalized.

2 comments:

Edmund Gosse is not a very reliable or objective critic to consult on Browne whatsoever, read his remarks on 'The Garden of Cyrus' for example, which he signally fails to understand and so condemns; also his ahistorical remarks on witchcraft, little more than slander and which contributed greatly towards the prejudice against Sir T.B. throughout the first half of the 2oth century.

Gosse has been recognised by many (read the remarks by James Eason at the penelope site on Browne for example) as the author of a bad critical book by an author whose barely-concealed hatred of Browne emanates from almost every page, hardly an objective perception can be found in it.

Far more laudable and healthier lit. critics to consult on Browne are the American scholars J.S. Finch, Frank Huntley and Norman Endicott.all of whom ARE worth reading.

American scholarship WAS at the forefront of Brunonian studies, but now sadly appears to be going backwards in its understanding of Browne, this is due primarily to the cult of W.G.Sebald in America, an author who is often the first introduction to Browne to american readers, thus engendering a delusion that Sebald possessed a critical appreciation of Browne; how much a man who wrote in German understood of Browne's baroque prose begs questions, simply identifying with Browne's alleged melancholia and admiring his labyrinthine passages of thought is insufficient literary comprehension.

Nor does reading Sebald help modern understanding of Browne either in recognising the achievements of Huntley and Green that the 1658 discourses are two halves of a diptych which answer and mirror in each other in imagery, truths and subject-matter.

In this context recent American editions by NYRB as edited by S. Greenblatt have rendered the reader of Browne a grave disservice, wilfully misrepresenting Browne's artistic vision. Whether this is misrepresentation originates from either wilfulness or ignorance hardly matters as the damage has been done. Amusingly I read somewhere that Greenblatt believes 'The Garden of Cyrus' to be a discourse on horticulture, probably the strongest evidence yet that he has not actually ever read the discourse whatsoever.

Browne has, in conclusion invariably attracted as many bad critics as good, and will continue to do while readers fail to recognise the the harmonious balance, not schism, between religious faith and science in Browne alongside the deep influence of hermetic philosophy and Christianity upon him.

Thanks for the Finch, Endicott et al. recommendations; I'll try and get them from the library. I should say that I wasn't citing Gosse as an impartial critic of Browne -- this should be clear enough from my post -- but more as an instance of Browne's "critical heritage." I would say something similar about Sebald or Borges. On the ca. 1900 view of Saintsbury and Gosse and Strachey, Browne is primarily admirable as a prose stylist; it is an odd fate for such a writer to have influenced chiefly foreigners, and to have come back to mainstream Anglophone consciousness through WGS. And obviously neither of these writers had a full critical appreciation of Browne. (Although this is partly beside the point; it is also true that Eliot didn't have a full critical appreciation of Donne or Marvell.)

I agree, of course, that it is irritating that the NYRB edition doesn't publish the Garden of Cyrus along with Urn-Burial, especially as it is so short; but the Garden is the least accessible of Browne's works, and Urn-Burial the most accessible.

Post a Comment